A parliamentary primary in Ghana’s Ayawaso East Constituency has ignited a storm of controversy, raising fresh questions about the corrosive role of money in the country’s politics.

Baba Jamal Mohammed Ahmed, Ghana’s High Commissioner to Nigeria, stunned observers when he announced his candidacy under the National Democratic Congress (NDC) following the death of the sitting lawmaker, Naser Toure Mahama, on January 4. Many had expected Mr. Mahama’s widow, Hajia Amina Adam, to inherit the mantle.

On February 7, five candidates contested the NDC primary. Pollsters had tipped Hajia Adam to win. But when the ballots were counted, Mr. Ahmed prevailed with 431 votes, edging out Hajia Adam, who secured 399.

The victory was immediately clouded by allegations of vote buying. Social media lit up with claims that candidates had offered delegates cash or paid for their travel. Mr. Ahmed drew particular scrutiny after reports surfaced that he had distributed 32-inch television sets.

Confronted by reporters, Mr. Ahmed (Baba Jamal) denied wrongdoing. “So if you give television sets to people, what is wrong with it? This is not the first time I am gifting things to people,” he said. “Those who know me know that every Christmas and every occasion, I have put down GHS 2.5 million to give free loans to people.”

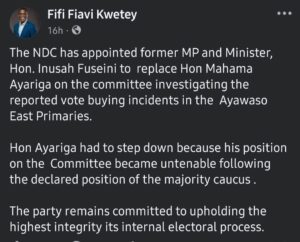

The presidency responded swiftly, announcing a committee to investigate the allegations and recalling Mr. Ahmed from his diplomatic post. The NDC majority caucus in Parliament issued a statement calling for the annulment of the primary pending the inquiry.

A Familiar Pattern

Vote buying is hardly new in Ghana. Candidates often dismiss accusations of bribery by describing cash handouts as “transportation allowances” or “feeding fees” for delegates traveling long distances. But observers say the practice is entrenched.

Section 33 of Ghana’s Representation of the People Law defines bribery as the provision of “money, gifts, loans, or valuable consideration” to induce voting behavior.

The persistence of the practice is tied to Ghana’s economic malaise. Inflation has eroded household incomes, making immediate material benefits more attractive than promises of long-term governance. A study in the International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science found that many first-time voters viewed incentives as a “deeply embedded social mechanism.” The report warned that such motivations “gradually erode their sense of political accountability and the moral obligation to act in the collective interest.”

The High Cost of Politics

The monetization of Ghanaian politics has created formidable barriers to entry. The Ghana Centre for Democratic Development estimates that parliamentary candidates may spend more than $693,000 to secure nominations. Presidential hopefuls face even steeper costs, with campaigns running as high as $150 million.

Such sums favor the most resourced candidates, often sidelining those with stronger qualifications but fewer financial means.

Reform Efforts

The NDC’s leadership has attempted to curb abuses. General Secretary Fiifi Kwetey recently announced that party members holding government positions must resign months before contesting internal roles, in a bid to prevent the misuse of state resources. The directive, however, came after Mr. Ahmed had already declared his candidacy.

The Office of the Special Prosecutor has pledged to investigate vote-buying allegations in both the NDC primary and the New Patriotic Party’s flagbearer contest.

Meanwhile, critics are pressing for deeper reforms. In a recent Brookings article, George K. Ofosu of the London School of Economics argued that delegates’ decision-making must be reshaped to reduce the influence of material inducements.

Others have taken their case to court. On January 23, cardiothoracic surgeon Prof. Kwabena Frimpong-Boateng, Dr. Nyaho Nyaho-Tamakloe, and former Minister of State Dr. Christine Amoako-Nuamah filed a lawsuit at Ghana’s Supreme Court. They contend that the delegate-based system used by the NDC, NPP, and CPP is unconstitutional and “oligarchic,” restricting voting power to a small circle of party executives and officeholders.

In an interview on Bullet TV, Emmanuel Wilson, leader of the pressure group Crusader Against Corruption, condemned the practice and commended the governing National Democratic Congress (NDC) for swiftly initiating internal investigations and delivering results within two days. He further urged the Office of the Special Prosecutor and the main opposition party, the New Patriotic Party (NPP), to adopt similarly timely approaches in handling such matters. Emmanuel Wilson contends that if political parties begin to correct this practice internally, the broader legal framework will naturally follow suit.

A Precedent in the Making?

With Mr. Ahmed’s victory under investigation, Ghana’s political establishment faces a test. Whether the NDC annuls the results, or the Special Prosecutor pursues charges, the outcome could set a precedent for how the country confronts vote buying.

For now, the practice remains deeply woven into Ghana’s electoral fabric a reflection of both economic despair and the high stakes of political power